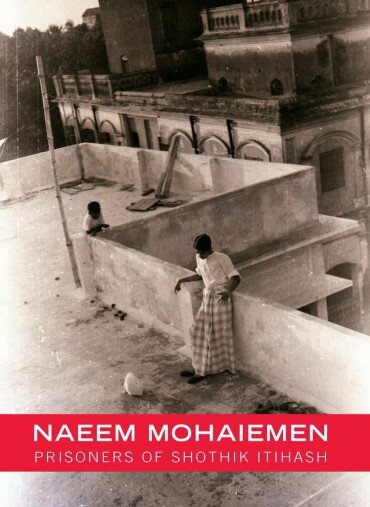

Author: Naeem Mohaiemen

Publisher: Kunsthalle Basel

Language: English

Pages: 96

Size: 22 x 16.5 cm

Weight: 250 g

Binding: Softcover

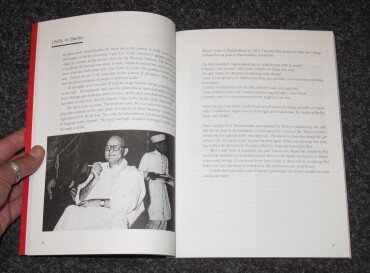

At a seminar in Dhaka discussing the anniversary of the war, an elderly gentleman interrupted me, stern finger raised high: ‘You must strive to present shothik itihash (correct history).’ At another event in Michigan, a professor said our generation was insufficiently respectful of the foundational history. Each time, I shivered and wondered who was going to decide for us, once again, what was and was not “correct history.“

In the last year of his life, bestselling novelist Humayun Ahmed was in New York, receiving cancer treatment at Sloan-Kettering. In the midst of chemotherapy, the courts summoned him, demanding to know why he had represented historical events “incorrectly” in his novel Deyal (The Wall). Perhaps weakened by his illness, or perhaps wishing for peace and quiet in his last days, Ahmed apologized to the court and promised to rewrite the novel when he had recovered. A month later, Ahmed died from severe sepsis after surgery. The novel was never rewritten.

It was left to journalist and poet Sajjad Sharif (in his enfant terrible college days, he had become famous for translating T. S. Eliot’s Wasteland) to argue for freedom of history in the Ahmed case: “French philosopher Alain Badiou said in his book 'Polemics,' power and creativity can never have a true dialogue with each other. In the final analysis, power is violent. On the other hand, creativity has no rule to follow except its’ own internal logic. When power faces off against creativity, it can only destroy that creativity.”

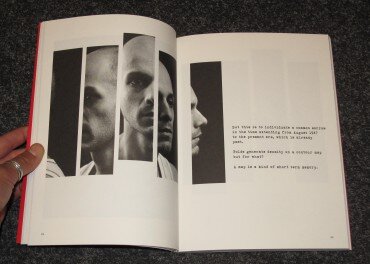

Naeem Mohaiemen’s films, photography, mixed media objects, and writing commingle major and minor histories in relation to the South Asian subcontinental triangle of nations, and the familiar histories of multiple partitions. Susan Buck-Morss recently argued that the Haitian slave revolt was the inspiration for Hegel's idea of the dialectic. But this argument can be taken further than Buck-Morss herself, to bypass the European Enlightenment altogether and establish Haiti's slave rebels as the root source for the concept of universal history. Inspired by the work of Haitian scholars, Mohaiemen argues that the history of the South Asian subcontinent provides a map for potentially universal trajectories of post-liberation reinvention.

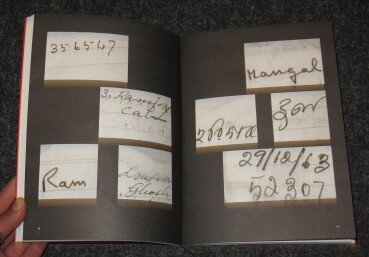

Mohaiemen's solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Basel, Prisoners of Shothik Itihash curated by Adam Szymczyk, pushes forward the idea of a different reckoning of universal history. This publication, twinned with the show, brings together essays and images by Mohaiemen that span the years 1929-1979, along with diary excerpts from "doomed" protagonists.